An in dept investigative look into commercial gallery spaces in London, through a podcast discussion with people working in and around galleries.

Links to downloads:

Link 1: Introduction:

Link 2: Episode 1 Conversation with Gabriela Giroletti & Hedvig Listøl:

DESCRIPTION PROJECT

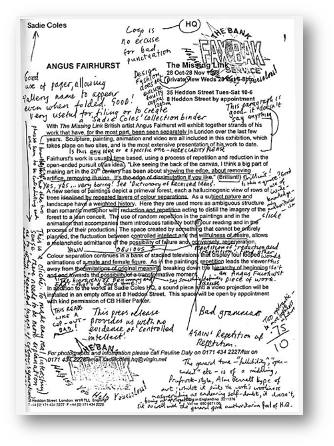

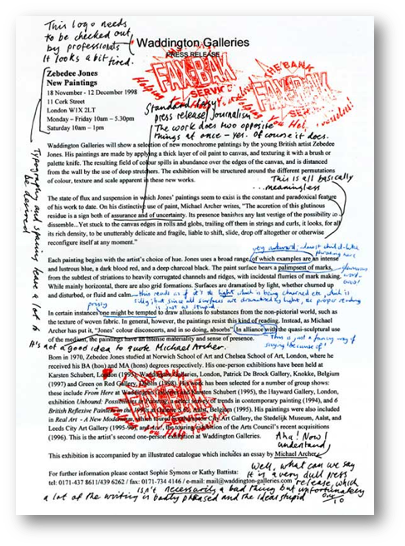

A podcast that could be commissioned by commercial galleries around London. The focus each time would lay on one exhibition. This show would be discussed in detail. The length of each episode would be around 40 minutes. The episodes will discuss the exhibition in great detail, presenting the perspective of everyone involved in the gallery, from the artist to the director to potential buyers or fans. This concept differes from other art podcasts, which often included interviews with an artist or focused on one museum show for a portion of the episode. This podcast will be in depth interviews centring on one gallery show and can serve as a counteract to reading the press release. The podcast will be available on Spotify internationally, for listeners anywhere and be able to be scanned at the entrance to the show and listened to after or while walking through the show. The inspiration of this project came from a lecture by Elliot Burns who talked about Fax Bak which was a collective in London invented during the 1980s that collected press releases of commercial galleries in London. Fax Bak used sharpies and markers to highlight and critique press releases based on the inaccessibility and phrasing of the text and faxed the marked text back to the gallery.

Following to the podcast episode there will be a “response” episode that will be a rereading of responses to the show that can be send in over a WhatsApp number either as audio files or text. Additionally, I would like to invite local students doing their A-levels in art to use the podcast format, walking through the show and contribute to the “response” episode. I believe that this project has the potential to make exhibitions much more tangible, exciting, and personal, avoiding the often inaccessible “art-language” of press releases and fostering a direct dialogue between artist and viewer and offering access to students interested in art.

I would love to have a response episode for each exhibition that would feed of voices of listeners sending in their interpretations about the interviews, podcast, the exhibition if they were able to check it out online or in person and the work itself. These responses could be send to a WhatsApp number as audio files or written text.

At the heart of this project sits the urge to engage on a deeper and longer level with the artist.

I believe gallery exhibitions should value the artists work and time, effort beyond the success of selling the show. I believe if we can change the way we engage with gallery exhibitions to include additions that prompt us to thing longer, deeper about the work that urge us to communicate about the work. If we spend time questioning the work and engaging with it.

To engage wider audiences, to have discussions and engage more people I believe we need more tools, in a sense more curation.

IDEATION PROCESS

Notes from the conversations from previous years

Think about the theme that you are passionate about

Take some care into the proposal (so you can use it for the hand-in texts)

Think about the medium and the idea that you have fun and are very interested in

Build on a detailed, small area and be very perfectionist and intricate about it

Think about possible partnerships

Think about something that you can distance from the dissertation research

Look at how you can and want to bring the project to live (means and how much time do you have in what medium do you want to work in/ means do you have think budget, time, collaborators et cetera)

Structure your research and where you store images, research, own writings

Trust the process

Don’t worry if it’s to weird

Have fun with the process

Immerse yourself in the project (find maybe something soothing)

Document everything you have done !!

Option 4 (Second idea):

A project that makes accessible gallery visits / press releases through audio guided podcasts

vision: a company, initiative that can be booked by the gallery: Gallery sent press releases, interviews with the artists or even the direct contact information with the artists

The initiative builds a podcast episode for each exhibition with time slots for when certain artworks within the show are being discussed

This could also be extended to a youtube channel with time slots and visuals from the show

This way the “art-language” of press releases can be avoided. A direct dialogue between artist communication and viewer that makes the exhibition much more tangible, exciting and personal.

Link: https://thewhitepube.co.uk/art-thoughts/why-i-dont-read-the-press-release/

SCHEDULED PLANNING METHODS

- Do a schedule / overview of by when I have to be done with the

- work in the next weeks.

– Ask Isabelle for an interview agreement brief document

—> Fill in and formulate the interview agreement according to the

participants

Do more visual research:

- mind maps for research portfolio

- Do my own version of critiquing press releases like FAX-Bak service

- AI generated texts? https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/ Specifically

About the exhibition (research):

- collect artwork images,

- press release for the show,

- Think about a script

- pdf press pack for the show,

- Biography & CV of the artist

- infos about the artist

- Background about millie

- Mission statement for the podcast .

Accessibility of the podcast, transcript

Do more theoretical research:

- Interpretation and Art

- Jerry Saltz renaissance —> how to view art

- The development of art influenced by interpretation and press releases

- looking at documenta 2022

- Art language

- Accessibility

- Higher art language

- The history of the press release

- Development of art podcasts

WEEK (5th March – 12 March 2023)

- Do more research into FAX-Bak and it’s contributors—> think about

writing an email to the FAX-BAK contributes to ask them a couple

of questions reflecting on their project, where they are now, how

this work manifests into what they are doing now, If they still - use any knowledge they gained from this experience, what galleries

- responded and generally the feedback they got about the work

- —> Doing a questionnaire for people about press releases for the

- research journal that investigates their opinions and understandings

- of press releases and their connection and feelings towards them

- Do Research into the artists practice that would want to participate

- Write the proposal email for Gabriela or Audun and for Hedvig

- Email the proposal to the artist I want to get involved with and ask

- Hedvig or Kristin and Millie if they would be up for helping or

- someone else in the gallery.

- Ask the journalist writing the press release

- PRACTICAL STATISTCICS

- Involve a graphic designer.

- Check if I can create the podcast jingle or do research

h how much it would cost to involve a sound artist - Do research how exactly I would record the audio (lend microphones

possibly) - If I write a script, a brief for the interview

- Where I would upload the episode which platform I would use.

- -(Holiday 19th – 22nd March 2023)-

- WEEK (12 March – 14 April 2023)

- Do the interviews with:

- – Artist

- – Gallery Director

- – (Writer/Journalist)

- – Collector

- WEEK (14 April – 1 May 2023)

- – Go into editing the podcast and size it down

- WEEK (1 May – 15 May 2023)

- – spend time to write the essay for the London Project

- – spend time to do the Research Portfolio

- DEADLINE: 15 of May 2023 is the deadline of the London Project

- 3 kinds of options

- Press release digest

- One long conversation

- With everyone involved in the show

- Wild card option

- Do more research into FAX-Bak and it’s contributors—> think about writing an email to the FAX-BAK contributes to ask them a couple of questions reflecting on their project, where they are now, how this work manifests into what they are doing now, If they still use any knowledge they gained from this experience, what galleries responded and generally the feedback they got about the work

- —> Doing a questionnaire for people about press releases for the research journal that investigates their opinions and understandings of press releases and their connection and feelings towards them

- Do Research into the artists practice that would want to participate

- Write the proposal email for Gabriela or Audun and for Hedvig

- Email the proposal to the artist I want to get involved with and ask Hedvig or Kristin and Millie if they would be up for helping or someone else in the gallery.

- Ask the journalist writing the press release

- WEEK (5th March – 12 March 2023)

- PRACTICAL STATISTCICS

- Involve a graphic designer.

- Check if I can create the podcast jingle or do research how much it would cost to involve a sound artist

- Do research how exactly I would record the audio (lend microphones possibly)

- If I write a script, a brief for the interview

- Where I would upload the episode which platform I would use.

- -(Holiday 19th – 22nd March 2023)-

- WEEK (12 March – 14 April 2023)

- Do the interviews with:

- – Artist

- – Gallery Director

- – (Writer/Journalist)

- – Collector

- WEEK (14 April – 1 May 2023)

- – Go into editing the podcast and size it down

- WEEK (1 May – 15 May 2023)

- – spend time to write the essay for the London Project

- – spend time to do the Research Portfolio

DOUBTS

QUESTIONING MY IDEA…

Think During the beginning stages of chaning my topic I felt very overwhelmed with ideas and questions, and tasks I needed to accomplish. Below is a stream of questions I noted down in my phone to figure out for the project:

Questions that I need to answer before I send out the emails

How long is each podcast episode?

Who do I want to involve and what purpose and response do I want from each

person?

Think about accessibility in language read about the background of art speak:

What does this podcast serve?

How long should it be?

It should be an intricate, more extended look at the exhibition not from a review

or article or an abstract text from of the press release but an interesting more

nuanced conversation with the entire team that is involved in the exhibition

Something that goes at length into the detail of the work that shows the

history and thoughts of people that put together the exhibition

Is there a way in from community groups or other people to also talk about

the work in this context? Is millie a valuable asset to talk too in this form of

the podcast? Think about before writing email to her…

She would tell me about her point of view what she sees in the work

and Gabriella but she jsn’t puts together the press release and references

so maybe she is not important to this version?

Email Natalie the proposal

text to get in touch with the collector

What inside to I want to hear from the collector research:

Check out the instagram how the person writes about art, what is important

to them when looking and collecting, buying art…

What would they bring to the conversation..

What does this person look at in the show

Things to do:

Do a survey

Do my own survey and ask people about how much information they collect at a show

Questions:

What they want to see in it. How much they care about the message, Does it have to be political

Do they need to know the artists story and background to be able to connect with the work?

Do they care about the institution do they want to know how they came to work together

Do they wanna know about the process of creating the show?

Send out emails tomorrow to Gabriela, hedvig, natalie!!

Maybe a separate episode of how other people connect to the work?

Should I split it into different episodes per interview so each person has their own episode they could click on for each perspective?

Listen to other art podcasts this is the questions they often asked:

Which is hanging on the wall?

What influenced the choice of works?

Motivation behind the works?

Which mediums, why?

Themes: Environment, pandemic, human proximity, memory, death, life, transience, different states, relationships → Other?

New themes in recent years? Motivated by current events? What influence did the pandemic have on your way of creating?

Exhibiting New possibilities? Other ways of creating?**

Over the years: Has the way of creating/inspiration changed? How? Why?

How did you find your way to art?*

COLLECTOR QUESTIONS: (check back in with other podcasts)

Are there important themes they focus on?

Do they have a focus in collecting?

Do they notice a certain feeling or thing when they know this is why they collect?

Do they try to reach out to the artists or do they wont to be kept distance form the talk and perspective of the work?

Can they become white obsessed with the work? have they formed close relationships with the artists? how much connect do they want from the show?

DEVELOPMENT AFTER FIRST PROPOSAL

In the past weeks I have spent time trying to deeply research each person participating in the mock-up episode of my podcast after writing a proposal email.

The first episode is going to compromise:

- Gabriela Giroletti who is a Brazilian abstract painter and sculptor and recently had a show at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

- Hedvig Listøl who has been the director of the London Bridge location of Kristin Hjellegjerde gallery since 2020.

- Pamela Hornik who is a collector who has previously collected art from Kristin Hjellegjerde gallery and is a prominent collector voice for accessibility of her own private collections in the USA.

I have send time reading articles, listening to podcasts, watching youtube videos of all three people and trying to become familiar with their background, passions and perspectives.

During and after I have comprised about 15 questions for each of them and emailed the questions back to each participants so they can get an idea before the interview. I have also given each of them a specific time frame until may for the interview. I have listened to the podcast by the Dephian Gallery interviewing Kristin, the galleries of Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery. I have listened to the podcast by The 8-bridges Podcast with Pamela Hornik.

Furthermore I have started to edit a website for the podcast and an instagram account. I have red the book Curator Conversations edited by Tim Clark and started reading the book Sensitive Caos by Tehodor Schwerk which was one of the main inspirations for the artist Gabriela Giroletti’s work. After April I want to work on the editing, the podcast jingle, the website, the logo and the collecting responses for the response episode, as well as record the introductory episode for the podcast that will introduce the podcast and it’s aims.

DEVELOPMENT DIARY

As a knowledgeable and motivated researcher, I am constantly seeking new ideas and inspiration for my work. However, after my previous hand-in and initial conversation with my supervisor, I realised that my original topic for the London project was too broad and difficult to tackle. This left me feeling shaken, as I had invested a lot of time and energy into the topic.

To move forward, I began brainstorming new ideas and documenting them in a pages document, marking each idea by number and adding any relevant details that came to mind. Although many of the ideas were based on my own neighbourhood or personal identity, they didn’t seem very tangible or easily realisable in a London-based project.

Eventually, I landed on the idea of creating a podcast that would focus on one exhibition in great detail, presenting the perspective of everyone involved in the gallery, from the artist to the director to potential buyers or fans. This concept differed from other art podcasts, which often included interviews with an artist or focused on one museum show for a portion of the episode. I also considered extending the project to a YouTube channel that would include visuals from the exhibition.

After discussing the podcast idea with fellow students, family members, and colleagues, I received positive feedback and enthusiasm for the concept. I believe that this project has the potential to make exhibitions much more tangible, exciting, and personal, avoiding the often inaccessible “art-language” of press releases and fostering a direct dialogue between artist communication and viewers.

As I continue to develop this project, I am excited by the possibilities and invested in the research process. I believe that with dedication and hard work, this project has the potential to make a real impact in the art world and beyond.

Development third hand-in

After receiving the feedback for my second hand-in that was a complete change in topic from the previous weeks I started to take action plans of what had to be achieved within in the next couple of weeks. This part of the process involved a lot of planning and strategising, looking forward and organising my time correctly. Time management and optimism for my projects are so crucial since I spend 3 other days working which really limits my time next to the Degree Group Project meetings, lectures, and the society I manage. I first made a weekly schedule setting multiple deadlines until the 15th of May.

At first I had to decide the first options of collaborators that I would want to bring on the podcast with me: the artist, the gallerist/ gallery director, as well as a fan or collector. Since I knew I wanted to speak to an artist from Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, the gallery I work for as well as have a professional interview dissecting the approach of the gallery with my gallery director I was very certain I would interview Hedvig Listol as the director. Furthermore I had made contact with some of the artists in the program and knew pretty quickly that I would love to speak to Gabriela Giroletti, who I had previously met and seemed open and talkative I knew about her way of researching and was sure she would be an interesting artist to talk to. Natalie gave me the tip to get in contact with Pamela Hornik, a collector from California in America with an outgoing personality, sits on boards, collaborates with museum exhibitions and wants to nurture contemporary art. After hearing about her I found out that she had also previously been in contact with Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery and that the gallerist, and director had spoken to her prior, which only made the selection of voices more reasonable.

After speaking to each collaborator and having them luckily agree to be part of the project. I send out an email with the draft of the project explaining everything in great detail. Thereafter, I took about 2 weeks to research, the gallery’s history, Pamela Hornik’s practice through articles and podcasts, social media as well as Gabriela Giroletti’s work and education through articles, youtube videos and read the research books she was inspired by for the latest body of works. From there I contextualised around 10-15 questions for each person adjusted to their interest and work and send them back for confirmation for the interview. On the 16th of April I conducted the first interview with Hedvig Listol at the gallery, lending a microphone from a friend from Ba CCC. I have been in contact with both Pamela and Gabriela to arrange the next two interviews in the next two weeks before I want to start going into editing in the beginning of May. From there I will have two weeks left to complete the introductory podcast, the 2nd episode with all collaborators, finish the website and instagram, jingle melody for the show and logo design.

| Episode with Gabriella Giroletti and Hedvig Listol | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Influence from other podcasts | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Podcast Making Artist Information accessible in commercial galleries | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Death of the Author | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Art writing | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Curator Conversations: Care for the artist | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Podcast Making Artist Information accessible in commercial galleries | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Art and Interpretation | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Future Plans Response Episode | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| International Art English by Levine and Rule | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fax Bak service | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arts and Politics: Arts Education and Underfunding | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Inaccessibility of Language | |||||||||||||||||||||||

ELLIOT BURNS LECTURE ABOUT FAX BAK SERVICE

| One of the main anchors of this project was Fax-Bak Service introduced by Elliott in a workshop in November 2022. The lecture already laid out a lot of the groundwork for the research I ended up doing.First and foremost it was Fax-Bak service explained on the next slides that grabbed by attention and which was the starting point for changing my topic in combination with the trigger if a recent press release text at a gallery. |

FAX BAK SERVICE RESEARCH

A POSITIVE EXAMPLE – GROVE COLLECTIVE

Personal impression

One very recent example from the 11th of May 2023, is the thoughts / Press Release shared by Grove Collective Founding Director Jacob Barnes.

Grove Collective is a new gallery and residency programme with founded in London that has recently expended to Berlin.

I really enjoyed the personal approach of the head curator using notes app, which is the same app many creatives use to note down streams of consciousness the emotions they feel but also things like grocery lists and poems.

The tone in which he writes is conversational like he shares his intentions about the upcoming exhibition with a close friend. It sounds earnest, passionate and personal.

QUIPLASH LECTURE 1 & 2 Ethics statement

Creative Access with Quiplash:

How to use plain language.

- Revisit that exercise of project ideation and see how your project has changed and what do you need to do

- Think about all the access, money, resources that you want and then see what access you would want to bring in

- What are our access non-negotiables ? I need / have to have/ want – if I don’t have these – the project doesn’t happen

- Here’s what I want to explore (ie I want to make a clubnight deaf people can participate in and enjoy). If I don’t reach my goal I still learned lots, so next time I have more information and so can achieve more.

- What is my – “I understand this is important but I can’t do it right now” – I don’t have the people / knowledge / money / time to make it possible right now.

Ethics Statement: + Quiplash workshop notes put in here

I am still doing research about the aim of access within my project and trying to grasp what access and care means from as many possible angles and perspectives of the project.

As my podcast aims to provide access to commercial gallery exhibitions that are generally seen as the shopping windows of the art world, where creativity, curation and care often seem to be left at the door I know that the term “access” can sound very presumptuous. The white cube space and cold establishment described by the white pube editors in “Why I don’t read the press release” Is afflicted with a white, male dominated history. In recent years many curators and more generally all art practitioners are fighting for a change in exhibition practice. I am well aware that my form of a podcast is not providing access in the most radical form but I hope it can provide a positive small-scale change to exhibitions within commercial galleries to provide a different medium that is audio-guided, and might help to be more engaging than written word. It provides access to people with vision impairment. Personally I can take in and remember information easer through audio then text – the podcast provides a second option to take in the information. It is important for the podcast to be language inclusive, with the help of lectures by the whiplash team and through ethic guidelines introduced by tutors, I am hoping to be aware of inclusive language. Within the podcast I will make sure to not use terms classified as “art-language” or “art jagon” and if terms are used to reiterate in editing and explain such points. Access within the space is something that is out of my person control but I will mention in the episode and on the website for the show.

Furthermore, I will provide a transcribe link on Spotify and on the website so that people with hearing impairment are still able to access the same information. I would like to spend extra care to adding extra visuals to the transcript of the different voices that are speaking.

During one of the tutorials at university I talked to other tutors, amongst them Hannah Kemp-Welch who is independently working on audience engagement project who critically questioned access in terms of voices represented within the podcast to provide accessible languages and positions. As the persons representing London galleries, collectors, journalists and many artists are speaking from a higher position of someone that has accumulated a lot of cultural and more than often come from a higher social and financial capital or come from wealth and has been part of the art scene. In that sense the voices representing such exhibitions might not always have the most accessible language. The responsibility seems to lay in my personal phrasing and choosing of the questions and the way the interview is led and edited. Furthermore Hannah mentioned the idea to talk to pupils, community groups about the work. Which lead me to the idea of a review/ response exchange.

This idea came from multiple tv shows, comedy channels, youtube videos that film a project and a response video. I am hoping the include this idea in my draft but might be short in time. I would love to have a response episode for each exhibition that would feed of voices of listeners sending in their interpretations about the interviews, podcast, the exhibition if they were able to check it out online or in person and the work itself. These responses could be send to a WhatsApp number as audio files or written text.

At the heart of this project sits the urge to engage on a deeper and longer level with the artist.

I believe gallery exhibitions should value the artists work and time, effort beyond the success of selling the show. I believe if we can change the way we engage with gallery exhibitions to include additions that prompt us to thing longer, deeper about the work that urge us to communicate about the work. If we spend time questioning the work and engaging with it.

To engage wider audiences, to have discussions and engage more people I believe we need more tools, in a sense more curation

ECTURE NOTES Podcasting: Passion, Research and Delivery:

Henry King at CSM – February 2023

Soundscapes for specific voices, and forming characteristics in the podcast.

Study Hacks:

- Write, draw, or record YOUR LEARNING & QUESTIONS

- Connect the learning to your practice & Share Knowledge as a team

- Connect podcasting to your research and assessment criteria

Conversations with Purpose to Inform, Educate and Entertain:

- Rant — getting out your opinions, issues, passionately and with little to no editing

- Oral History — recording someones else’s story, a few prompts, some research, very little editing

- Documentary — On location investigative piece grounded in research, including experts & witnesses

- Opinion Piece — one side of a debate, not necessarily factual

- Interview — Researched/ focussed conversation

- Fully produced — Themes, research. A team, fully scripted, carefully timed and rehearsed

What are you qualified to talk about?

Have someone to talk to and who listens: Share my experience of visiting a certain cultural event and discuss the themes I spotted and discuss them, review them, form a critique (student age/ entry level)

Who do I do this for?

People also passionate about the same event, friends I know, people that create artists (student age/ entry level

Someone to communicate with, share their passion, converse about the same topic, connect with others

Reach out their platform

How do they change as a result?

Gain a new connection, new friends possibly?

More people interested

Hopefully gain knowledge from each other

What research have you already done and what research do you need to do?

What I have done:

Background into the collective that criticised press releases

Other press releases

Other podcasts that are good examples in interviewing artists / people in the art world

Theory research into art speak and why people don’t find it accessible

Research I need to do:

Which exhibition show I want to use as an example; when it will take place

In the next two weeks (20th February – 5 March):

Submit the proposal (24th March 2023)

Check if I can create the podcast jingle or do research how much it would

cost to involve a sound artist

Do a schedule / overview of by when I have to be done with the work in the

next weeks

Ask Isabelle for an interview agreement brief document

Ask the artist of the show if they want to participate and have an option B

and C prepared

Ask the gallery director or gallerist if they want to participate

Ask the journalist writing the press release

(5th March – 12 March 2023)

Involve a graphic designer

Do Research into the artists practice that would want to participate

Do research how exactly I would record the audio (lend microphones possibly)

If I write a script, a brief

Where I would upload the episode which platform I would use.

(Holiday 19th – 22nd March 2023)

(12 March – 14 April 2023)

Do the interviews with:

Artist

Gallery Director

(14 April – 1 May 2023)

Go into editing the podcast and size it down

(1 May – 15 May 2023)

Write the essay for the London Project

Do the Research Portfolio

15 of May 2023 is the deadline of the London Project

Task: Creating your podcast

- Use your life Purpose Sentence:

- Create a list/ Mindmap of 10+ episodes

- List discussions

- List interviewees

- What is the problem / query you address

List of Episodes (Examples):

— Introduction to the podcast

— Gabriela Giroletti solo show “Mingling Currents” at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

— Audun Alvstad solo show “As if you had a Choice in the Matter” at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

— Nabil Anani solo show “The Land and I” at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

— Kwadwo A Asiedu solo show at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

— Grayson Perry “Posh Cloths” at Victoria Miro Gallery

— an artist at a London gallery

Section in the episode (whole episode 30-40 minutes)

- Introduction

- Concept of the show with the artist

- Concept of the show with millie the journalist

- Background of the artist with millie the journalist

- Walking through the show with the artist

- Analysis of two works in the show: close description

- Interview with the director of the gallery background of what they like about the artist, how much they have worked together etc etc

- Walking though the show with fan / collector who shares their thoughts

- Links to where to find out more about the show and the artist

PODCAST RESEARCH HOW IT IMPACTS US

Over the past 5 years I have developed a deep passion for listening to podcast, especially with the rise of streaming services such as Spotify, I have grown very fond of consuming information about my interest into art exhibitions, politics, cultural theory, film through podcasts. They have become an integral part of my research into any kind of uni project, might it be essays, interviews or researching future employees and collaborators before job interviews. Especially during the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and during the months of isolation podcasts served as a connection point on solo walks around London; during commutes on the underground. Even as my part-time job as gallery assistant our entire team continues to keep up with art world news, or entertainment through pop culture podcasts. Our team stays motivated and connect during office hours through such co-listening sessions. There are hardly any days that pass where I don’t listen to at least one podcast a day while commuting to work, uni or while cleaning, cooking, or doing other daily tasks.

Growing up in Germany, I have been influenced by the importance of audiobooks. As many people describe Germany as a society of audiobook listeners even before the rise of the podcast through streaming platforms. During my early childhood most children I knew listened to Benjamin Blümchen, Bibi Blocksberg, Bibi und Tina, Die ???, TKKG — all stories that were primarily known in audio formats.

This trend never stopped during my years into adulthood as it was common amongst my friends even in our teenage years and during sleepovers to listen to and fall asleep to detective shows such as Die Drei ??? Or the “girly” equivalent Die Drei !!!, both detective shows. Other shows included Conni and Conni & Co audiobooks about the same girl growing up ranging from her experiences through kindergarten, primary and secondary school. Funnily enough if you currently look at Germany’s iTunes Charts you will notice that the top 10 albums are still often dominated by these children audiobooks, the most famous one being Die Drei ???. A detective show around three boys growing up in Los Angeles and solving crime cases in their teens. As an international pop act trying to climb the charts to the number 1 spot often serves difficulty pushing such audiobooks of their top placements.

Inspirational podcasts

Gemischtes Hack is the biggest German language speaking podcast, and the most listened to European podcast that’s not spoken in English. The format is a weekly catch—up conversation between two male comedians, Tommi Schmitt and Felix Lobrecht in their mid 30s popular through comedy shows that discuss their lives, German culture and politics, and their everydayness in a very comedic and playful, down to earth way using very “common” language. They have succeeded at building up a strong listener community through additional engagement on their instagram accounts and their acknowledgments of fan pages that draw the themes of the episode, create memes et cetera.

The Art Newspaper podcast, as well as The Art Angle Podcast is a structured art podcast with usually up to 4 different segments of different people talking about exhibitions, interviewing participants, breaking down what happened in the art world, auctions, exhibitions, openings, museums et cetera. The Art Angle is a very similar to the previous podcast also a selection of news segments that vary from monologues to interviews about the art world.

The podcast titled by Spotify & Süddeutsche Zeitung podcast titled Wirecard: 1,9 Miliarden Lügen (transl.: Wirecard: 1,9 Billion Lies) that goes over two seasons, in total 12 episodes each around one hour long discusses the biggest recent German credit card scandal in great depth and investigation with a large team of producers and journalists. The podcast that takes an in depth look at germans biggest international finance affair. It is a discussion between two journalists with interview segments of other participants, each episode having a specific theme, linear going through the development of the crime over 2 seasons and 8 episodes per season in total lasting over hours twelve hours.

The podcast Alles gesagt by ZEIT , one of Germany’s other biggest newspapers is a collaboration between two of ZEIT’s most established journalists Christoph Ahmend, Editorial Director of the ZEIT magazine and Editor in Chief of ZEIT online Jochen Wegner. Each month they invite a high-profile guest of Germany’s media, political, intellectual landscape. They research this guest in great depth with an entire team from the newspaper beforehand. The show itself can last from 3 up to 10 hours — the rule is the episode doesn’t stop until the guests says the “stop word” that they set at the start of each interview. Overall, the atmosphere of the show is set out to be very relaxed. The language is very conversational — furthermore each episode features games and restaurant deliveries that are being brought in; a whole dinner is consumed while recording the interview. The guests might they be some of Germany’s biggest politicians, artists, art collectors, authors, actors, et cetera are supposed to let loose and go into in depth conversations about their work, their personal life; their upbringing (if they want to) and current cultural happenings. Usually the podcasts last between 4 and 10 hours per episode.

Each of the above named podcasts were key references to how I would proposition my own podcast. I wanted to bring together a symbiosis of all these different characteristics of these shows. The main attributes that I noted could be characterised as 1) conversational

2) comedic, personal

3) easy, comprehensible language

4) Interview Formats

5) In depth, investigative discussions

6) Understanding the inner thoughts, psyche of the interviewee

7) In general longer formats all these are at least 40 minutes up to 10 hours per episode

Translation into CCCG- Conversations on Curating Commercial Galleries podcast:

After noting down all the strengths of these different podcasts I tried to acknowledge how they informed and shaped my approach towards the questions and approach of interviewing for my own podcast.

All these different podcasts shaped for my own project to become rather conversational. I wanted the interviews to be focused and critical but also to introduce new themes and aspects very smoothly and easily. The selection of which question was asked was based on the previous answer the interviewee had given. It was a conscious effort to try and incorporate my own voice and experience into the podcast when it was fitting. I was conscious of not taking up space or interrupting but at the same for it to feel more conversational, friendly and a close connection between friends, rather than individual people as that was the inspiration I had taken from all shows mentioned prior.

I was aware of making the setting comfortable leading up to the interview I reminded the interviewees Gabriela and Hedvig that they could stop and repeat their answers any time or take breaks if they wanted to. Before starting the interview I made sure to create an easy conversation with them about their week to build an easy transition between small talk and catch up hours to asking my questions. I advised interviewees be as natural as possible to be aware of not using art language “art jagon” terminology and that they are allowed to swear, or drink while recording, and should laugh as much as they want, every thought was welcome I was the happier the more blunt and straight-forward they expressed themselves.

I incorporated personal questions in the beginning to make them loosen up and to be able for them to freely retell their memories and background.

PODCAST RESEARCH HOW IT IMPACTS US

Wework

Seven reasons why podcasts are dominating the media landscape

October 9, 2019

Wework talked to Mr. Brewer – founder of a celebrity and influencer management agency, a model and talent agency, who hosts the podcast Lipps Service, for which he interviews influential names in music and pop culture—to understand why podcasts are dominating the media landscape. He listed seven points as to why the podcast is succeeding during the decline of Television, radio and other media traditional media formats.

Firstly the podcast is accessible as it is readily available to listen to without preparation from your smartphone at any time of day. Apple Podcasts, Apple’s podcast-streaming app, comes built-in on the iPhone—no download necessary. The music-streaming giant Spotify also introduced a dedicated podcast section on their platform. To listen to a podcast, you don’t need to buy a book, a Kindle, a cable or newspaper subscription. For most of these platforms, listening to a podcast is completely free on a device most people own anyways. Secondly, podcasts allow you to multitask doing multiple things at the same time such as working, running errands et cetera. As podcasts come in all different lengths, they can serve as a recap of the political news for 2 to 10 minutes or serve as a 10 or 3 day series through an entire road-trip. you can take a deep dive into, say, a nature podcast that teaches you how trees speak to each other with an episode that keeps you entertained for hours on a road trip. Even from the side of the creator podcasts are easy to produce as the main tool is a microphone. Many podcasts have launched out of basements, living rooms, and kitchens. Furthermore streaming services offer endless versatile interests for podcasts.

Another reason is the intimacy that podcasts build to their listeners. Many high-profile guests, celebrities have given more inside into their personhood through podcast shows that otherwise would be extremely unreachable. The accessibility for many people to become their own producer has enabled many public personalities to become reachable. Brewer says “When you’re listening to a podcast, you feel like you’re sitting around the dinner table with these people,” he says. “And that’s intoxicating.” The closeness of having someone speak directly to your ear at any time anywhere and be able to play anywhere can build on an intimacy or para-social relationship towards the speakers. Therefore podcasts easily build communities coupled with the niece topic, interest of each episode many podcasts work through emotive and personal stories, many shows are completely unscripted different from many traditional media formats that such as tv productions, that involve a large crew a podcast can be made up by one, two, three people. This sense of community is supported by a community that patiently awaits the release of a weekly update (or more/ less dependent on their schedule). Many podcasts develop a real fan community through added signifiers such as merchandise; community instagram profiles that share updates, memes about the recent discussions; many of them organise their own podcast tours; meet-ups, and discussion groups. Furthermore podcasts are easily adaptable to change transform based on the reception of the audience. The producers can easily change and adapt their format in order to fit the wishes of their listener audience this way the community builds further trust and relationships. It tells the audience that they are value.

PODCAST RESEARCH HOW IT IMPACTS US

In 2017, London School of Economics’s Christine Garrington explained in her post ‚What 10 years of producing podcasts with social scientists has taught me’ the power of podcasting as an impactful research tool for the future.

It’s never been easier to create, edit, and upload a podcast and an increasing number of academics are using it to showcase and share their research. Christine Garrington explains why podcasting is such a powerful and impactful tool for researcher.

Saying that, it struck me very early on that these audio interviews released over time with a format similar to a mid-morning radio interview were potentially a great way to communicate research and increase its potential for impact.

A decade on, I have produced podcasts on the world’s largest longitudinal study and how it’s used to benefit society; a programme of research designed to reduce inequality between men and women; genetic testing for breast cancer; children’s health and development; and the role of evidence in human rights advocacy, the most recent series of which is working to end modern slavery by 2030. I don’t think podcasting can get much more impactful than that! One of the most popular podcasts I produce is all about research methods! Who knew?

But what is it about podcasting that works so well when it comes to sharing research and showcasing and achieving impact?

The most recent RAJAR report, which analyses audio listening in the UK, sheds some light on this, explaining that podcasts.

The RAJAR report also notes that people who commute, exercise, struggle to sleep but need some relief from the blue-white fuzz of a computer or smart phone still require stimulation, concluding that “podcasts fit our lives in a way that virtual reality headsets may never. They liberate our eyes”.

There’s something quite personal and intimate in hearing a researcher talk about their work, especially in a conversational setting rather than in a presenting situation – it can help bring complex ideas and issues to life. As long as a researcher can talk confidently and accessibly about their research, adding context and comment where they can, this can really help non-academic audiences get to grips with those ideas and see how they relate to them.

Reaching a global audience

Audience research figures in the US estimate that 112 million people have listened to a podcast at least once. 67 million are listening to podcasts every month; 42 million do so every week. Those listening on a weekly basis listen, on average, to five different podcasts.

Here’s the Oxford English Dictionary definition and it’s a great place to start:

PODCAST RESEARCH HOW IT IMPACTS US

And here are a few more things to think about:

- Just as you would think about potential beneficiaries in a grant bid, think about who is going to benefit from your podcast.

- Set up a Facebook group and Twitter account not just to share but to engage – get ideas and feedback.

- Consider the format and aims of your podcast before you switch the microphone on. For example, the human rights podcast I produce has a clear aim “to get the hard facts about the human rights challenges facing us today”.

- Think about tone and style – will your podcast feature hard-hitting interviews, fireside chat, edgy conversations, or quirky commentary?

- Let each episode tell a story that has a beginning, a middle, and an end.

- Think in terms of series – say, one episode a month for 12 months for Series One.

- Invite and consider feedback from listeners along the way and ask yourself what worked and what didn’t.

- Newsjack – is the topic of your podcast in the news today? Join in the conversation and point to episodes of your podcast that might be of interest.

- Get some professional training or support – write this into your grant bid; there are lots of great courses.

Podcasting is perfect for people with big ideas

There has never been a better or more exciting time to be podcasting and to be using podcasts not just to share research findings but to really engage with people interested in getting the hard facts about the many challenges facing the world today. But what’s more important is getting the subject matter, aims and format of your podcast right in the first place, and you do that best by thinking about and engaging with your audience from the outset.

One thing I have learned in ten years of podcasting is that podcasts are more about communities engaging than being a simple a vehicle or tool for communication. Viewed that way, podcasts have the potential to put you right on that pathway to impact.

Christine Garrington is a freelance consultant with extensive experience collaborating with social science researchers to maximise the impact of their work. She co-edits a number of research focused blogs and specialises in the production of podcasts for research centres and individuals around the UK and in the States. She also manages a number of social media accounts for research projects/blogs and produces compelling print and digital content for researchers and centres that clearly demonstrates actual and potential benefits to research users.

DEATH OF THE ARTIST / AUTHOR SEGEMENT RESEARCH

The death of the artist link to medium article: https://medium.com/counterarts/the-death-of-the-artists-8db3909f62f1

The Death of The Artists

The Birth of The Viewer Must Be At The Cost of The Death of The Artist

August 23 2021

Roland Barthes famously noted in his 1967 essay “The Death of The Author” that: the birth of the reader must be at the cost of the death of the author. The same research can be translated to the death of the artist and birth of the curator or critic. The conversation has extended well beyond the 1980s and still proves relevant and transferable today. The initial writing of Michel Foucault’s 1969 “What is an author?” to the writings of postcolonial theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak’s writings on the author as a relation of temporality.

Roland Barthes responds to his own inquiry with the argument for the death of the artist; It is the language which speaks, not the author. In equally complicit terms, it is the art which speaks, not the artist. The artist is no more or less than a tool in which great art is created. The artist should inherently experience their own death, for their art to be born and flourish, lest their conscious presence detracts from the art itself.

The artist’s death is synonymous with that of the author, insofar as both play, even perform the same roles in their creation: they are the new “medium” through which works of literary fiction or artwork are conceptualised, channelled, created.

Not to mention potentially being audited for my claim to having degrees in art history and curatorship; death to my career I guess.

The artist must be nothing more than a “medium” through which art flows through, allowing for pure expression devoid of the artist’s ego. The artist and their artwork’s symbiotic relationship must suffer in order for the art to flourish, to stand alone, to withstand the changes of time.

DEATH OF THE ARTIST / AUTHOR SEGEMENT RESEARCH

Michel Foucault Death of the Author:

Podcast episode

New Books in Critical Theory Podcast

Death of the Author 1977, published Image Music Text, tranl: Stephen Heath, new York: Hill and Wang, 1977

Death of the Author by Roland Barthes

The intention of the author doesn’t matter. Authority intention doesn’t exist. The birth of the reader must be at the cost of the author.

This idea has crept into our way of thinking. We are willing to privilege, prioritise and belief our own interpretation over any authoritative narrative set out by the creator. In order to do any good close reading / criticism what you are looking for when you are looking at the specifics / details is not for an omission author, who is incredibly good at putting all the details in, you are not looking for the best but you are looking for the ways in which language acts through the author. You are building your own opinion not looking at what the author was looking for but what you can see in the work.

In some cases the biographical details of the author are quite important in the way they read the texts. Individual subjectivities and interpersonal relations are less individual then we assume them to be and are much more interconnected by shared experiences and interpretations. Society and our interpretations and thoughts, opinions are that much more socialised then we think. That image of the networked world. There is a discussion about the individual vs the society – the way that we imagine ourselves acting as individuals in terms of the social contract; and individual agency and potentially if we didn’t

think of ourselves so much as individuals to begin with, we would not be so worried and focused on maximising and exclaiming our individual interest.

The responsibility of the reader is actually really important topic to think about. If we can’t expect responsibility from the writers ( political figures) of our public discourse then we can perhaps shift responsibility on our readers by necessity the responsibility also has been shifted on to our readers in the way we consume things, which writers we give attention and who dominates public debate.

The best line: “In fact the answer on how the death of the author could make a positive impact. “In precisely this way, literature it would be better from now on to say writing by refusing to assign a secret – an ultimate meaning to the text – and to the world as text – liberates what maybe called an anti-theological activity and an activity that is truly revolutionary, since to refuse to fix meaning is the end to refuse god and his hypothesis: reason, science, law.”

Barthes’ point is that we cannot know. Writing, he boldly proclaims, is ‘the destruction of every voice’. Far from being a positive or creative force, writing is, in fact, a negative, a void, where we cannot know with any certainty who is speaking or writing.

Indeed, our obsession with ‘the author’ is a curiously modern phenomenon, which can be traced back to the Renaissance in particular, and the development of the idea of ‘the individual’. And much literary criticism, Barthes points out, is still hung up on this idea of the author as an individual who created a particular work, so we speak of how we can detect Baudelaire the man in the novels of Baudelaire the writer. But this search for a definitive origin or source of the literary text is a wild goose chase, as far as Barthes is concerned.

In so far, this research theory of the death of the artist relates to my research into interpretation, press release as a sheer representation of this development over time.

Nowadays, the idea of the death of the artist is a constant in the discussion about art and artist as well as discourse.

Nowadays, there is a tension between the focus on the author / artist and their thoughts = the discourse they start and the work itself and the discourse the work and interpretation of the reader / critic starts.

Another current tension exists in the readership and which discourse / artist / artwork gains attention and money, extended readership and if they deserve or have owned this discourse as well as ways to disown the power they have achieved through attention.

All in all, the theory behind the death of the author is an interesting one when Roland Barthes argues for the author to step back and let the work take centre stage as something that is flexible and which’s meaning changes throughout time and societal, historical developments then I do strongly agree with this approach.

Nevertheless my project does not argue for the death of the author / artist and their “authority” voice over their own work rather I argue for a longer attention span to truly grasp and care for the thoughts of the creator and from their build a new discourse that is not necessarily dependent on the authority voice set out by the artist but builds towards flexible engagement with the work and community building through interpretation, attention and care of the work instead of immediate labelling or judgement.

ARTIST RESEARCH

Information about Gabriela Giroletti (b.1982):

- Brazilian painter

- Lives and works in London

- In 2018 Master in Fine Art (distinction) from Slade School, UCL

- 2019-2020 Honoary Research Fellow UCL, Slade School

- In 2015 graduated from Middlesex University in Fine Arts (first class)

– Themes within past work you explored the themes of… The relationship between the painted image (the meaning, the immaterial, the metaphor, the mind) and the material presence in the painting (the corporeal, the touch, the physical presence, the body). Paintings fluctuate between their crude materiality and their metaphysical aspect, encouraging the viewer to formulate peculiar connections with our tangible surroundings, as well as with individual and unique lived experience.

INTERVIEW QUESTIONS GABRIELA GIROLETTI

Hello Gabriela welcome to the podcast. I am very excited to speak to you today.. I want to begin from the very start…

Questions:

- How did you develop an interest in art?

- What was your route to working as an artist?

- What is the most valuable skill you required from working as an artist?

- What does it mean to be an artist in an age of image excess and such a highly competitive industry?

- Can you describe what kind of atmosphere, impression you wanted to express with the paintings in this show “mingling currents”?

- Themes: Theodor Schwenk’s book Sensitive Chaos: The Creation of Flowing Forms in Water and Air describes the relationship between water and air and their relationship to biological forms

- The title of the exhibition “Mingling Currents” comes from a passage that you found particularly inspiring can you tell us about this passage and what it sparked for you.

- When did your interest in nature, biology arose in art was it from the very beginning?

- Does it serve as a further escape from the busy live in London to research and refocus on such close biological mechanisms?

- All the works in the show have a very specific textures. Some are very sleek and shiny like “magnetic fields, sea above” and others have very thick layers of paint such as the series of miniature paintings with very thick oil paint layers; and then other works in the show like ”The Natural, Here and There” extend over the canvas with wooden pannels attached to the outside. Can you tell us about your fascination with texture and the combination of sculpture and painting?

- How was the selection of these works inspired were they created as a close collective concept or quite separate from each other?

- Have paintings been motivated by specific experiences, and happenings over the past year?

- How has your approach developed in practice but also maybe has your research/inspiration/method of inspiration changed?

- What is the most memorable exhibition you have seen yourself?

- What was an important exhibition for you to take part in?

- What is the myth that you would like to dispel around working as an artist?

- What advice would you give other artists that are just starting out at uni?

GABRIELA GIROLETTI CV INFORMATION

“MNGLING CURRENTS” EXHIBITION IMAGES

“MNGLING CURRENTS” EXHIBITION IMAGES

MNGLING CURRENTS” EXHIBITION IMAGES

Exhibition MINGLING CURRENTS

10 MARCH – 15 APRIL 2023 at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

Brazilian artist Gabriela Giroletti’s luminous, elemental paintings are rooted in the emotional experience of being in nature. To stand amid her paintings is to enter a shifting landscape, to tunnel deep beneath the earth or to become submerged in a shimmering pool. Mingling Currents, her second solo exhibition at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, presents a new series of translucent, fluid forms that explore the sensations and movements of water – flowing currents, rippling light, weightlessness and depth.

While Giroletti’s work emerges from and responds to periods of introspection, Theodor Schwenk’s book Sensitive Chaos: The Creation of Flowing Forms in Water and Air formed an important point of reference for this latest body of work. The book explores the subtle patterns and phenomenon of water and air and their relationship to biological forms – the title of the exhibition comes from a passage that Giroletti found particularly inspiring and which discusses the ways in which everything is interconnected and in constant flux. Keeping these ideas in mind, she used paint in a very spontaneous and vigorous way in an attempt to translate ‘some of nature’s potent energy’ onto the canvas. The result is a series of curved, stacked and overlapping forms that seem to simultaneously emerge from and sink beneath layers of translucent colours. Though we might glimpse something familiar in the shapes that we see, she retains a deliberate ambiguity to evoke a sense of slippage and wonder. ‘I try to dance between different possible meanings so people will read my work using their lived experience,’ she says.

While Giroletti has previously worked with deep, earthy colours, this latest body of work is both lighter in colour palette and atmosphere. Layers of translucent paint create an appearance of radiance while also allowing the viewer to glimpse through the surface to the marks beneath. At the same time, the canvases remain textured, full-bodied, almost gritty at times, as if capturing sand or stones tumbling through water. Bodies, like most real-world details, are stripped away, but we feel almost as if we are being pulled into or washed over by the paint. They’re paintings that seem to spill over their edges to envelop both viewer and surrounding space.

These contrasts between different depths and materialities, between stillness and movement are central to Giroletti’s approach to painting. She is interested in transitions and borders – the points at which things meet, intermingle, gain form or collapse into shapelessness. As she puts it, ‘I’m exploring the idea of whether the work can be painting and sculpture at the same time.’ This is most obvious in the works where she has extended the painted surface by attaching sculptural objects to the stretcher bar that appear like bits of rock, coral or shell, but even those without added elements, evoke a space far vaster and more tumultuous than the stiff linen that contains them.

It is this expansiveness that makes the paintings so compelling – they are caught in a never-ending process of transformation. Shape-shifting, churning and illuminated, what these works capture is not one moment or thing, but the pulse of life in all its strange brilliance.

Research artist Exhibition “BREEZY” at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

Research artist Previous Exhibition “BREEZY” at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

Research artist Previous Exhibition “BREEZY” at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

19 NOVEMBER – 18 DECEMBER 2021 at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery

Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery is pleased to present Breezy, a presentation of new paintings by Gabriela Giroletti at the gallery’s Wandsworth location. Breezy is Giroletti’s first solo presentation with the gallery and is on view from November 19th to December 18th, 2021.

To look at Giroletti’s work is to be enveloped in an animated terrain where swollen masses with shimmering surfaces writhe and crawl, locked into what seems like a territorial competition. In amongst the maelstrom roots get diverted, growths get stunted and billowing excesses crunch into each other. Our vantage point onto this world shifts from painting to painting. At times we appear to be above ground. At others we have fallen down a rabbit hole and are tunneling under the earth. But as we turn the burrow’s bends the walls shift like tectonic plates before transforming back into sky, revealing the inside to have been outside all along.

Giroletti is interested in the notion of the in-between and the paintings are full of things on a journey from one state of being to another. The landscape undergoes its restless mutation and the forms that inhabit it often seem to be expanding beyond their capacity or deflating as the animating energy leaves them and moves onto something new. Indeed breeziness, the sense of movement in the flickering planes that are to be found throughout the work, is itself an in-between condition; neither windy nor still, Breezy accelerates and decelerates indecisively between the two.

This stirred motion is rendered by layers of translucent directional brushstrokes of varying hues that build into a diaphanous pointillism. In “Heat Haze”, for example, streams of fizzing dots intermingle generating ripples of modulating intensity and in “Spatial Places” these dots throb and scatter like water droplets on a train window. Radiation or gaseousness come to mind, not least when the skies gleam amber orange or sap green.

The smaller works are more fragment-like. They lean towards inert mineral colours, like charcoaled fossils or bits of rock. In paintings like “Tralalitions” or “Last Not Least” the paint is heaped, dug and scraped making the surface seem like part of an excavation. Here, subtle variations of tone poke through the mottled texture, echoing the optical energy of the larger paintings.

Spatial disjuncture is another theme that underlies the work. In the smaller pieces, devices that are reminiscent of collage techniques, like cuts and fold-ins, are experimented with. In “Some Things Cosmic II” for instance, thick seams appear between the forms, stitching them together into assemblages. Also an adjunct, in the form of a perched mound of paint, materialises on top of the stretcher bar as an extension of a shape within. This causes the painting to flip ambiguously between pictorial space and objecthood.

These experiments get scaled up in the larger works where they evolve further. In “Transparent Things”, for instance, the seams between the forms are accompanied by an overlaid fade and a drop shadow. Both elements have widths that remain constant all the way round, stamping out the edge, emphasising its status as a border. And in “Compass”, dark orbs, that start out by hugging internal thresholds within the picture, escape and re-appear as separate panels on the wall. This melding together of different spaces creates an array of formal possibilities. As we witness the development of the devices from painting to painting, we start to imagine what it would be like if we combined them differently, taking a bit from one painting and placing it on another, like pieces in a board-game.

The use of emptiness in the work also conjures up this sense of possibility. Although Giroletti draws from everyday life when conceiving her compositions, most real-world details are stripped out, leaving the shapes with smooth striated surfaces. Giroletti doesn’t seek to represent the specifics of particular objects so much as the relations between them. This use of voids, cuts and in-between states is what makes the arrangements inherently open and playful. The viewer feels on the verge of stepping into the frame, picking up one of the forms, and participating in the world building themselves.

PROPOSAL EMAIL FOR ARTIST, GALLERIST, JOURNALIST

Participation in a podcast episode about the exhibition “Mingling Currents” by Gabriela Giroletti running at Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery, in London (London Bridge) from the 10th of March to the 15th of April 2023. The podcast’s aim is to create a dialogue between creators of the exhibition and the visitor / collector, the episode will be sectioned into interviews with the artist, the gallery representative, and the journalist writing about the show. As an avid podcast listener and a frequent visitor of museums and galleries, I have noticed the necessity and in/accessibility of the press release has been a question that arises every time during my visits and work. This is why I propose an exhibition guide for galleries in the form of a podcast that challenges the use of the press release as the primary tool for information about the exhibition.

Similar to the press release, the podcast could be played while visiting the show and scanned via QR-code at the entrance to the gallery. The podcast is a collaboration between the artist, the gallery director, and additional collaborators such as further representatives of the gallery, long-standing collectors or fans of the specific artist. The episode brings in multiple perspectives addressing the concept of the show, the development, the history of the gallery working with the artist, and closer descriptions of a few pieces in the exhibition. The idea behind the podcast is to provide a more accessible, detailed and personal approach to inform collectors, gallery visitors, as well as people not aware of commercial galleries about the work of the artist. The goal is to spark conversations about how we can make art more accessible and engage a wider audience.

Bring them in, convince them to participate…

In conclusion, I believe that an exhibition guide podcast is an excellent way to make art more accessible to the public and to collectors, bringing multiple perspectives into the episode and providing honest and intricate information about the exhibition. While the podcast is not meant to replace the press release or many of the duties, it is an excellent addition to it, and it would provide a more nuanced understanding of the art pieces, artists, and the exhibition as a whole.

(A conversation is to be had about the agreement of publishing. I am personally very happy if you would participate. The episode could stay unpublished and serve as a mockup / draft for a potential real show, and would only be heard by professors of the University of the Arts London or could be published to the public on Spotify or could also be agreed to be available for listening at the gallery.)

Script episode 1 and 2 introduction

Episode 1

“The exhibition’s title is derived from the Einsteinian notion of a time wrap – the distortion of space/ time. Rather than traveling radically up or down the longitudinal axis of time, this exhibition examines the latitudinal notion of the weft (weave’s past tense), which, in textile production, continually doubles back in itself. IN this manner the exhibition explores recurrence – the way, to extend the metaphor, a wefting thread, transversing through the wrap, may over the course of a life realign with aspects of itself, years on; the way, in a tapestry, this same phenomena creates an image or pattern. The new paintings function as repairs or weaves or sutures in the failure of language, just as the prose-poems in the exhibitions’ titular book repair the failures of image. Like the metaphorical fabric referenced in the title. It is in the interplay between these two disciplines that an auto- portrait or auto-analysis begins to emerge, For instance how does desire conveyed in language differ from image, where affect circumvents denotation?”

-music-

The previously read text is a recent press release from a commercial art gallery in London from the year 2023. It starts with an academic reference including scientist Albert Einstein and talks about abstract themes such as space, time, language, phenomena, and life. The text mentions metaphors and the difficulty to translate visual material into text. This press release presented a perfect example of any other press release or gallery text that one finds in contemporary gallery spaces in London.

-music-

This project wants to question is this the best way of communicating the information of an exhibition, as well as the artist, and their works? Are there better ways of informing gallery visitors, collectors and journalists about an exhibition?

-music-

Welcome to the first episode of CCCg or conversations on curating commercial galleries” this is an introduction into the podcast.

-music-

My name is Antonia Scharr and this podcast is part of my final degree project in my Bachelor’s from Central Saint Martins College in Culture, Criticism and Curation.

-music-

s part of the submission asks to plan a project that closely links the research, themes of our past three years of study and engages with London’s communities I chose to focus on a frustration I have felt within galleries, art fairs in London. The inspiration of this project came from a lecture from November 2022 by our tutor Elliott Burns who talked about Fax Bak Service. Fax Bak was a collective in London invented during the 1980s that collected press releases of commercial galleries in London. Fax Bak used sharpies and markers to highlight and critices press releases based on the inaccessibility and phrasing of the text. They focused specifically on the snobbish and “art jagon” language of such texts. Art Jagon since then has been characterised as terms that are only used within art writing in reviews, articles but especially press releases.

-music-

A graduate project composed as part of BA (Hons) Culture Criticism and Curation at Central Saint Martins by Antonia Scharr. The focus of each episode will be on one singular exhibition. The pursuit behind each episode will be an investigative discussion on the artist and gallery collaboration discussing in detail the way each person works and what they have learned from their practice. The exhibition will present the perspective of everyone involved in the gallery, from the artist to the director and hopefully listeners and visitors. This podcast will be in depth interviews centring on one gallery show and can serve as a counteract to reading the hard-to-understand press release. The length would be dependent on how much inside each artist is willing to share about their, research, the process, personhood et cetera. Central to the purpose of this project is the use of conversational tone and standard English as opposed to International Art English “Art Jagon” used in Press Releases.

-music-

A QR-code is presented at the entry of the exhibition so listeners will be able to choose if they want to scan and listen to the interview after, or while walking through the show. The inspiration of this project came from Fax Bak Service which was a collective of London artists invented during the 1990s that collected press releases of commercial galleries in London. Fax Bak Service used sharpies and markers to highlight and critique press releases based on the inaccessibility and phrasing of the text and faxed the marked text back to the gallery.

Following to the podcast episode there will be a “response” episode that will be a reading of responses to the show that can be send in over a WhatsApp number either as audio files or text. I believe that this project has the potential to make exhibitions much more tangible, exciting, and personal, avoiding the often inaccessible “art-language” of press releases and fostering a direct dialogue between artist and viewer as well as hopefully offering access to students interested in art.

A transcript of the entire episode can be found in the description of each episode together with other visual extra materials

-music-

Script

Episode 2:

‘Mingling Currents’ is the second solo exhibition by Brazilian painter Gabriela Giroletti at the Norwegian contemporary art gallery Kristin Hjellegjerde in London. Gabriela’s work is a mix of miniature and large-scale abstract paintings with shiny, thin and thick layers of oil paint spread on the canvas. The current show continues Gabriela’s exploration with biological elements and the textures of water and air and how they are interchangeable with so many of nature’s processes and textures.

-music-

The second part of this episode is a discussion with Hedvig Listøl, Director at Kristin Hjellegjerde’s London Bridge space. The episode is an in depth discussion with both artist and gallery representative about their work, collaboration, thoughts about the works, thoughts and experiences in the art world laying open certain work dynamics, myths about working in the arts and the overall feelings about the show. You are listening to a podcast created by Antonia Scharr as part of Ba (Hons) Culture, Criticism and Curation’s graduate project at Central Saint Martins in London.

-music-

This project sets out to be a timely conversation about what it’s like to work in London’s art scene and a closer look into the development of a gallery show. The pursuit for investigative and forrow looks at artists and exhibitions is the main narrative behind this show, centering on the artist and their feelings and path into the arts. This format supports open communication, accessible language without academic terminology to filter through the pretentiousness of other similar formats.

-music-

Editing and Producing was by Antonia Scharr, Sound Design was by artist Peter Spanjer. Sound assistance was by Maja Renfer.

Thank you to artist Gabriela Giroletti, gallery director of Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery Hedvig Listøl for speaking to us and all their support and kindness towards this project. I also reached out to art collector for an interview Pamela Hornik but were not able to arrange a time.

-music-

Hedvig Listol, is the director of Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery in London Bridge. Kristin Hjellegjerde was founded in London, Wandsworth in 2012 and since then has expanded two a second location in London Bridge, third permanent space in Berlin, Germany and will open its 4th permanent space in west palm beach , Florida in October 2023. The gallery focuses on representing contemporary artists mostly painting, textile work and sculpture with a strong technical and theoretical background to their work..

-music-

Artist Gabriela Giroletti was born in 1982 in Brazil. She currently lives and works in London. In 2015, Gabriela finished her Bachelors in Fine Arts from the Middlesex University in London. Afterwards she moved on to continue studying a Masters degree in painting from UCL – university college London at slade school of fine art where she also held a position as honorary research fellow from 2019 to 2020. Gabriela Giroletti’s art explores the relationship between theoretical research and material presence in the painting recently focusing on biological transformations and nature’s elements.

-music-

You have been listening to a podcast produced by Antonia Scharr as part of BA Culture, Criticism and Curation at Central Saint Martins.

Background about Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery